AfterBirth

Afterbirth is a small bundle of zines, all A7, held together loosely by a belly band. The zine has been Risoprinted in Red and Black.

Slipping off the belly band, I separate the three zines. They all have the same front and back cover – a red swirl, drawn in pencil, that looks almost like a curved folded ribbon, with handwritten title ‘Afterbirth’ in black, bordered by small straight lines that are dashed out to form a sort of halo of fine lines around the title. This style of title is replicated on the bellyband, and throughout the zines.

Two of the zines are bound the same, and a third is bound with staples.

I open the stable bound zine first.

The stables hold together an assortment of different paper.

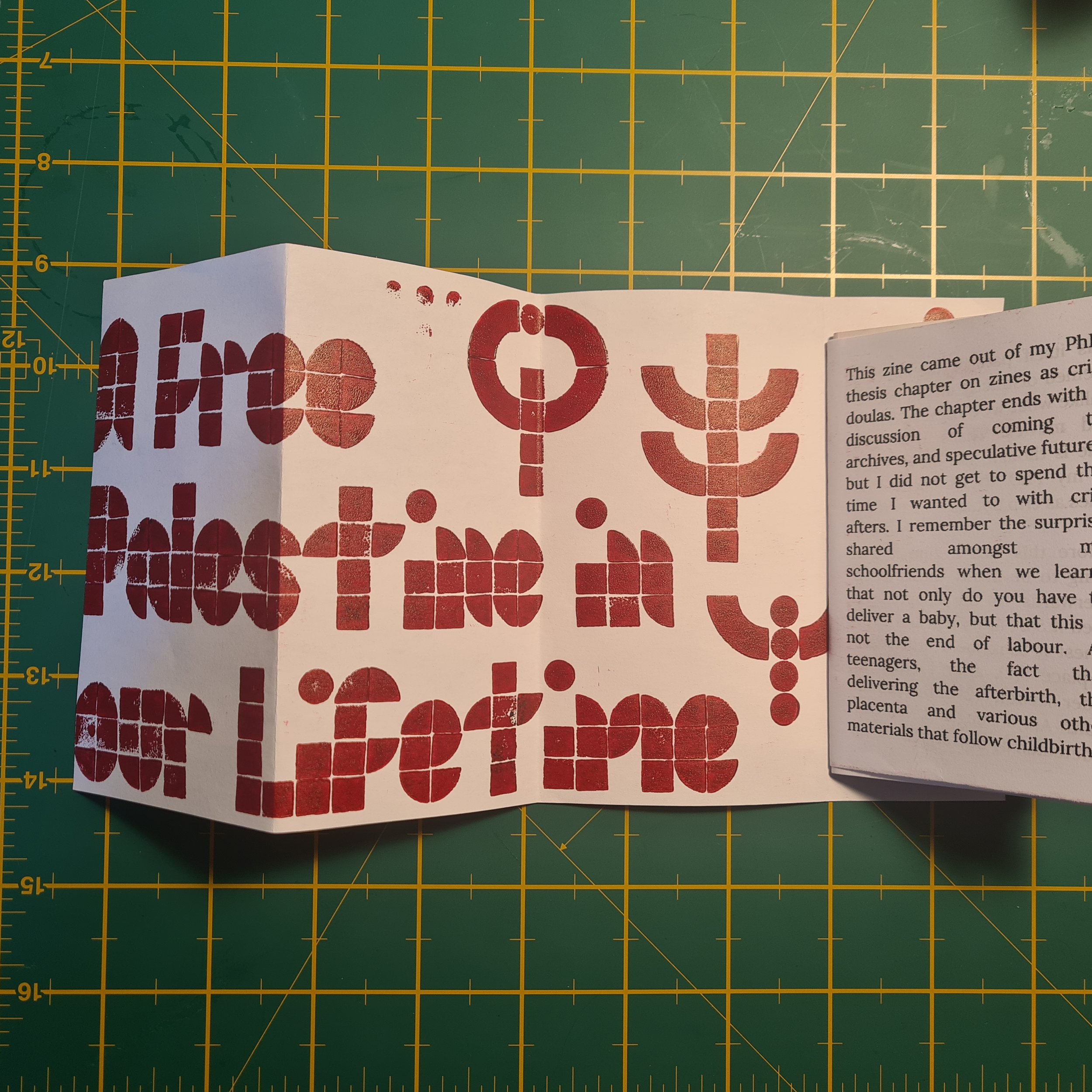

Unfolding the first insert strip reveals a horizontal print, in a deep burgundy, that was created using lego and so looks almost pixellated. It reads ‘A free Palestine in our Lifetime’, beside strange lego plant-like shapes. I fold the insert back in.

Printed black and white text on the following pages reads:

Pg.1

This zine came out of my PhD thesis chapter on zines as crip doulas. The chapter ends with a discussion of coming to archives, and speculative futures. I remember the surprise shared amongst my schoolfriends when we learnt that not only do you have to deliver a baby, but that this is not the end of labour. As teenagers, the fact that delivering the afterbirth, the placenta and various other materials that follow childbirth,

Pg.2

was itself part of the process seemed distinctly unfair, so unlike what we’d been sold in tv and movies. That’s what this zine is though, the meaty extra to my PhD thesis chapter on zines as crip doulas.

Before it was a zine it was going to be in my thesis as an afterwards to the chapter. I’d titled it 5(2). Afterbirth and to be honest it took me a little while to place 5(2), after I typed it. Under section 5(2) of the Mental Health Act, in England, you can be detained by doctors in

Pg.3

hospital for up to 72 hours, during which time you should receive an assessment that decides if further detention under the Mental Health Act is necessary. It is more commonly called ‘Doctors Holding Power’. It can only be used if you are already an inpatient – in my experience I have had it applied when I’ve been admitted to a general hospital to treat and manage the effects of an overdose, and I’ve tried to leave once I’m medically fit. I’ve also had it threatened as an informal patient on a psychiatric unit, if

Pg. 4

I tried to leave. Section 5(2) is a temporary suspension, a period where you are held, waiting for the formal assessments that make up a (typically) Section 2 MHA assessment.

When I started my PhD I thought of zines as places to imagine futures - different worlds or ways of being, utopias. As if there was a paucity of imagination, as if, if we came up with the right idea, could only visualise it, construct it from cut-up magazines and with old sharpies and rubber stamps, we could get there.

Pg.5

sharpies and rubber stamps, we could get there.

After running several versions of the same workshop with various climate organisations over the winter of 2020/21, I rapidly grew tired of talking utopia. Maybe I didn’t do it right. Maybe it’s because I’m not very good at imagining the future in my personal life. More likely, I think, the problem we face is not an inability to imagine different futures.

Pg. 6

In October 2020 I read Tao Leigh Goffe’s ‘The DJ is a Time Machine’ – the second of a three-part series Far Futures which used ‘science fiction and other futurist thinking to explore the possibilities of other worlds, or the strangeness of this one’.

The next page is an insert of thicker paper, Riso printed in black and red. It fold out to a longer strip. The same folding ribbon twists and swirls down the length of the insert. Hand written text in black over the top reproduces (imperfectly) the text of Diane di Prima’s Revolutionary Letter #2:

The value of an individual life

A credo they taught us

To instill fear, and inactions

‘you only live once’

A fog on our eyes, we are endless as the sea, not separate,

We die

A million times a day, we are

Born a million times, each

Breath life and death:

Get up, put on your shoes, get started, someone will finish.

- Diane di Prima

Pg.7

Goffe describes an activity they led with their students – challenging them to think about what it would mean to curate a museum in the year 2350: ‘To curate the past in the future, as I enticed my students to join me in doing, is to position oneself as not only a time traveller, but as an ancestor.’

I started asking, in zine workshops, what does it mean to be someone’s past, and what do we want them to inherit?

P.8

Now, I don’t want to run zine workshops at all. I’m tired of it. It feels impossible to imagine the future.

Does writing about trans-ness in terms of liminality, in terms of becoming, just make the focus on transition? I worry sometimes that writing about liminalty and in-betweeness makes it impossible to be born? What is the after or beyond of this?

Pg.10

Julian Carter, asks, in response to Sean Dorsey’s dance work Lou:

Rather than imagining transition as a linear progression, what would happen if we imagine transitions between genders, like choreographic transitions, as places in time in which numerous movements—forward, backward, sideways, tangential—are equally possible and can coexist?

P.10

It’s a metaphor, isn’t it? Birth, birthing disability.

But I can’t stop thinking about actual birth. I guess because Abi and I are trying to have a baby and so many of the conversations and tests and delay is in making sure that the baby isn’t going to be disabled. It makes me worry about letting them see me as disabled, as the person who would be carrying the child, because I know they screen for the exact same thing in donors

P.11

And that these things discount you as a donor – where possible, we select them out the gene pool and its so fucking weird to have to answer questions about how we “chose” our donor because submerged underneath these questions of how tall he is or what colour his hair is is just…eugenics.

P.12

Crip time doesn’t make you patient. In thinking of crip afters, it doesn’t meant you don’t want it now. Crip time means we want it not only now, but in the past, already, want to fold time over on itself to offer it back.

The back cover continues the swirling red ribbon. There is a handwritten quote from Alison Kafer in black, haloed by finelines, that reads “Can we tell crip tales, crip time tales, with multiple befores and afters, proliferating befores and afters, all making more crip presents possible?”

And the date: 2024.

The other two zines are both folded like OS Maps, with the covers (repeated across all three zines) cut and stuck on front and back. Unfolding both reveals a square sheet with black and red riso illustrations on one side. Where the sheet is folded (into twelve even rectangles) the riso ink has slightly smudged.

The first I unfold is based off watching a short set of excerpts of Sean Dorsey’s dance work Lou – there is a title ‘Lou (excerpts)’ in the right hand top corner that mimics the youtube video’s title screen for this work. There’s the play button bar across the bottom of the square, screenshotted and replicated from Youtube and the image is covered in the middle by a pop-up that reads ‘”youtube.com” is in full screen. Swipe down to exit’. In between large curving structures (that look a bit like you’re inside a Barabara Hepworth sculpture), drawn in black pencil, echoing the folded ribbon of the front cover, figures dance in red pencil (other than three seated figures at the front in black) – these figures were drawn directly from the excerpts I watched. Sometimes they are easy to distinguish as individual dancers, and sometimes their forms blur together. At the very back, partially visible behind dancers and folds, is text from a typewritten letter between Lou and Virginia. This is kind of an illustration, kind of a comic but all happening at once, kind of a map: some kind of attempt to document my experience of watching this dance, that Julian Carter’s notion of folded time is based on, but mediated by youtube, and only in partial fragments.

The second map also unfolds to a single sheet Black and Red riso illustration/comic.

Halo’d text in black at the top reads ‘Where do I go from here?’ on the left and ‘Afterbirth’ on the right. On the right side, a set of hands reach up to hold a bloody placenta. One of the arms has a gaping black slit in it. The background is curving red swirls again, but the pencil strokes are more definite, and they don’t fold in on themselves so much as curve and bend like a river. Layered above this is a map, like the flatlay of a dungeon you’d have in Role Playing Games, with thin black tunnels between the rooms. The rooms are labelled, from left to right, fractions, ford, furrow, orchard (these were the names of rooms in a Labyrinth at a church in Kaunas I visited). On the top layer, there is an illustration of an egg, a figure, seemingly giving birth to rabbits that sprint away from them, watched over by a cut and pasted figure from an engraving, who’s been given red bunny ears. He’s looking down at the birthing figure holding a cup of tea, and a speech bubble reads: a great birth. This collaged figure is from Hogarth’s illustration of Mary Toft from 1726, Toft apparently gave birth to rabbits, but Hogarth uses it as an opportunity for satire, poking fun at medical incompetence. It’s from Wellcome Collection’s online images (public domain of course). On the egg, text reads: there is only one route through a labyrinth. The birthing figure responds ‘that’s how you learn faith’.